I have many documents created with Microsoft Office for assignments written for graduate school courses years ago. How can I easily convert those dozens of documents to a different format without using an online application? This is an excellent example of the power of open source.

Five years ago I took a course at a local university where all of the documents were provided in ‘docx’ format. Is there a way to convert those documents to an ‘odt’ format? There is and it is quite simple.

$libreoffice --headless --convert-to odt *.docxWhat if I decided I wanted to convert those ‘docx’ items to ‘html’ so they could easily be shared on my classroom website. What if I had wanted to convert all those documents to html?

$libreoffice --headless --convert-to html *.docx

I can use the same tool to turn those ‘docx’ files into ‘pdf’ files with an iteration of the same command.

$libreoffice –headless –convert-to pdf *.docx

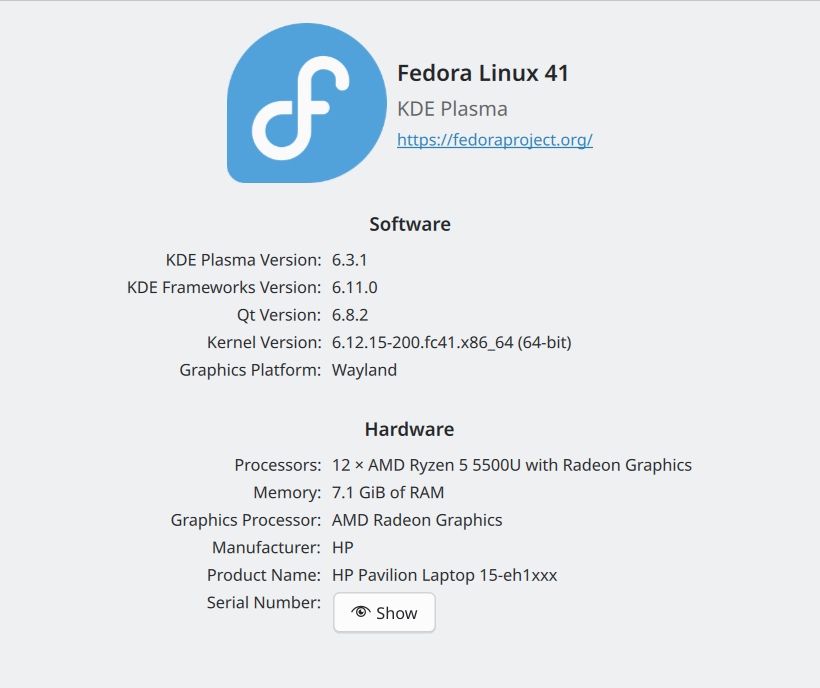

Using LibreOffice from the command line inside the directory where the files you want to convert is easy and the conversion is accomplished in a matter of seconds depending on your processor and memory. You can find many more uses of LibreOffice from the command line by entering the following command on your own command line if you have LibreOffice installed as most Linux distributions do.

$libreoffice --helpThis is a great example of the power of open source software.